Developing the UT-Series Transformers

Around the same time that Terry Manning and Oliver were deciding to build the Lucas CS-1 microphone, Terry was also talking to Larry Janus of Tube Equipment Corporation (TEC) about building a mic pre under the Lucas brand name. Larry had built custom compressors used in the studios in which he engineered in the early 1980’s. Admiring his work and knowledge Terry asked Larry to build a specialized mic pre that would follow a similar idea as the CS microphones; a classic inspired circuit that could have been built in the golden days of audio, but for some reason nobody had built it. Larry had just the project which is now known as The Moonray.

When Terry asked Oliver if he could build the transformer for The Moonray project Oliver said sure. We’re always happy to help out Terry and admired Larry’s knowledge on the Fairchild series of compressors. What Oliver didn’t know was that Larry had built the first few Moonray prototypes around new old stock A-series transformers made by the United Transformer Company (UTC). Meaning he already had a specific tone in mind that he was trying to achieve.

Over the years Oliver had rewound a couple of those all-American transformers but mostly the ones used as Pultec outputs and in the Fairchild's side-chain. When Oliver first spoke to Larry, to get a general idea about the circuit topology and which transformers he was looking for, it did not sound too difficult. However, the one twist was that not all UTC transformers sound the same. There were several revisions and later versions were built entirely differently. The challenge was that Larry and Terry wanted to replicate a specific sound from a specific early revision of the UTC that had a “buttery” low end. Without direct documentation of that specific revision this was now an experiment in how to replicate a transformer from a sonic signature as opposed to looking at build documents.

The first step was to buy a bunch of different vintage A-type transformers off of ebay to test them and try to map their general design. Without taking them apart, it did appear that UTC had produced several revisions over the years. A few displayed that rich, buttery low end that Terry and Larry had described to me but they all seemed minutely different from each other. Just by measuring the electrical aspects of the transformers it was difficult to determine the winding style. However, during the first tests, it seemed that the secret might lie in the types of magnetic alloy used.

Unfortunately, a few months went by without any progress due to AMI being locked up with CS microphone production. But during that time, I bought several broken UTC transformers on e-bay. I then dropped my collection of those gray, black and light green cans in a vacuum bath of solving agent while vibrating them at 60Hz for a couple of weeks. This removed the very sticky bitumen so the transformer could be retrieved from its can without breaking any leads.

Before opening them, Oliver guessed that they had used UI type lamination. The dynamic tests that Oliver had performed earlier on the working UTC transformers indicated that the short inductance was 90 degrees out of phase; a property that is only displayed by UI, DU and LL type cores. But knowing that LL cores are rarely used in audio and DU cores were mainly used for miniature magnetic applications, the UI core was the best guess. And it turned out to be correct!

Next came the biggest challenge; unwinding the transformers! Oliver had to map out all of the leads to their right location, size and termination. As it turns out, with most of the broken UTC transformers it would have been quite easy to fix them up as most of the open loops were due to corroded wires and any steady handed repair tech could have reattached them. But the goal was not to fix them but map out those classic winding patterns. To Oliver's surprise the winding balance from core to core was quite good especially for mechanical winding machines of the 1950’s and 1960’s.

After Oliver was finished with the winding scheme, the main attention was now on the cores themselves. The slight difference in overall winding turns from revision to revision was due to the different types of metal alloy used in the different revisions. This also explains the difference in sound from transformer to transformer. The quickest way to determine the metallurgical make up is just to weigh the lamination on a manufacturing scale and with two reference pieces where the approximate amount of NI/FE is known in each lamination sample, the balance can be calculated. The final answer can also be done via a spectral analysis but in this case, the weighing method revealed the final answer. Once Oliver had all of this information, it was time to make some transformers!

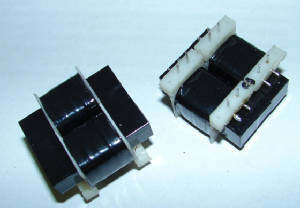

The first samples were done for reference measuring reasons only, with no effort or attention spent on cosmetic correctness. The main goal was to make a 100% sounding copy of the “buttery style” UTC transformers that Larry wanted to use for The Moonray with looks being a secondary factor. So fortunately, Oliver did not have to follow the yellow brick road of replicating it in every physical aspect. I was able to use a very similar European-sized lamination that we already use in production instead of custom ordering the vintage type lamination.

Today the main challenge on procuring lamination is being able to meet the minimum requirements of the lamination manufacturers. Fortunately, the UI type that we use on a daily basis would work for this transformer so the minimums were already being met. Due to the closeness of the European size to the original, the basic winding scheme could be followed and after a few in-house trials the first technically identical transformer with reference to frequency sweep measuring was done. I then made two additional samples for Larry and sent them to him.

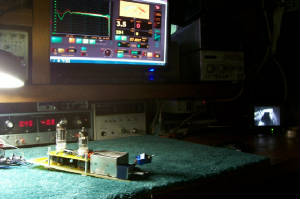

Larry’s reaction was quite positive, but he could still correctly pick which transformer was which in blind listening tests every time despite matching frequency specs. He told us that if we could not get it closer he would still use our transformer as he liked their sound. But we wanted to meet Larry’s original challenge! After he sent to me static and dynamic test results that he had performed, I had to work with him on a language that could quantify sound in a manner that we both understood. Based on this information exchange, we then sent him a second set of transformers the following weekend. While they were closer, Larry could still tell them apart. This was turning into a fascinating experiment…

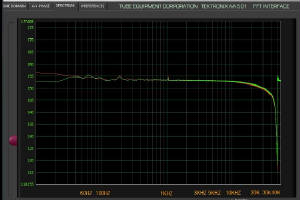

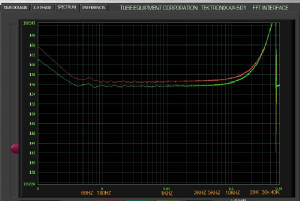

One of the hardest tasks is to compare transformers. A good beginning is to have an identical frequency plot, but after that there can be still so many other differences in sound even when the frequency plot looks almost identical. One of the difficulties is how to measure the core alloy of a transformer and how it affects the sound. There are not many dynamic test procedures if any that can determine what difference the core composition does to the sound. Larry and I started with FFT measurements, carefully taking into account the relation of amplitude vs. phase shift at the different levels. We fine-tuned those measurements so that we ended up with a resolution that could display the difference of just one piece of lamination. We then tried various mixes of plain steel lamination with the different Nickel alloys.

It took quite some time to dial it in, but when we were done we could enhance the saturation in the low mid frequency range without compromising the frequency response at all. It is almost like changing the resolution for that particular frequency band. Once we nailed the output transformer it was easy to develop the input transformer and the plate choke.

From the beginning of this project, Larry pointed out that he thought that there is a good market for vintage UTC transformers. Dealing with aftermarket and DIY iron for quite some time now I was not too convinced but the prices on eBay for old stock units were quite impressive. I started to call around to friends and OEM customers to find out their opinions. The overall response was that yes, A-series type transformers are great for one offs and DIY projects. These same folks claimed they would use them if they were readily available, and while they do color the sound, it is in a pleasant way that most people are familiar with. So with getting the A24 and A26 virtually identical to the historic originals all what was left was to work on the A10.

The last concern was the fit and finish. Fortunately, the familiar shape of the square can was used all throughout the US electronics industries, so several suppliers of the deep drawn can are still in business. The solder lugs are also an off the shelf Keystone part so getting the fit and finish right was easier than we had feared. We did a few alterations from the original design but our units are still direct replacements for the historic transformer in technical specs and physical dimensions.

As a result of all this work, we unveiled our latest editions to our aftermarket catalog at the AES Show in NYC Fall of 2011. We plan on offering our UT10, UT24 and UT26 as stock items in 2012 and we will use the same can for other reproductions of classic irons such as the transformers that made the vintage Neve module world famous.

You can purchase our UT10, UT24, and UT26 here.

Also Read: